Hello! I’ve been thinking about the terminal a lot and yesterday I got curious

about all these “control codes”, like Ctrl-A, Ctrl-C, Ctrl-W, etc. What’s

the deal with all of them?

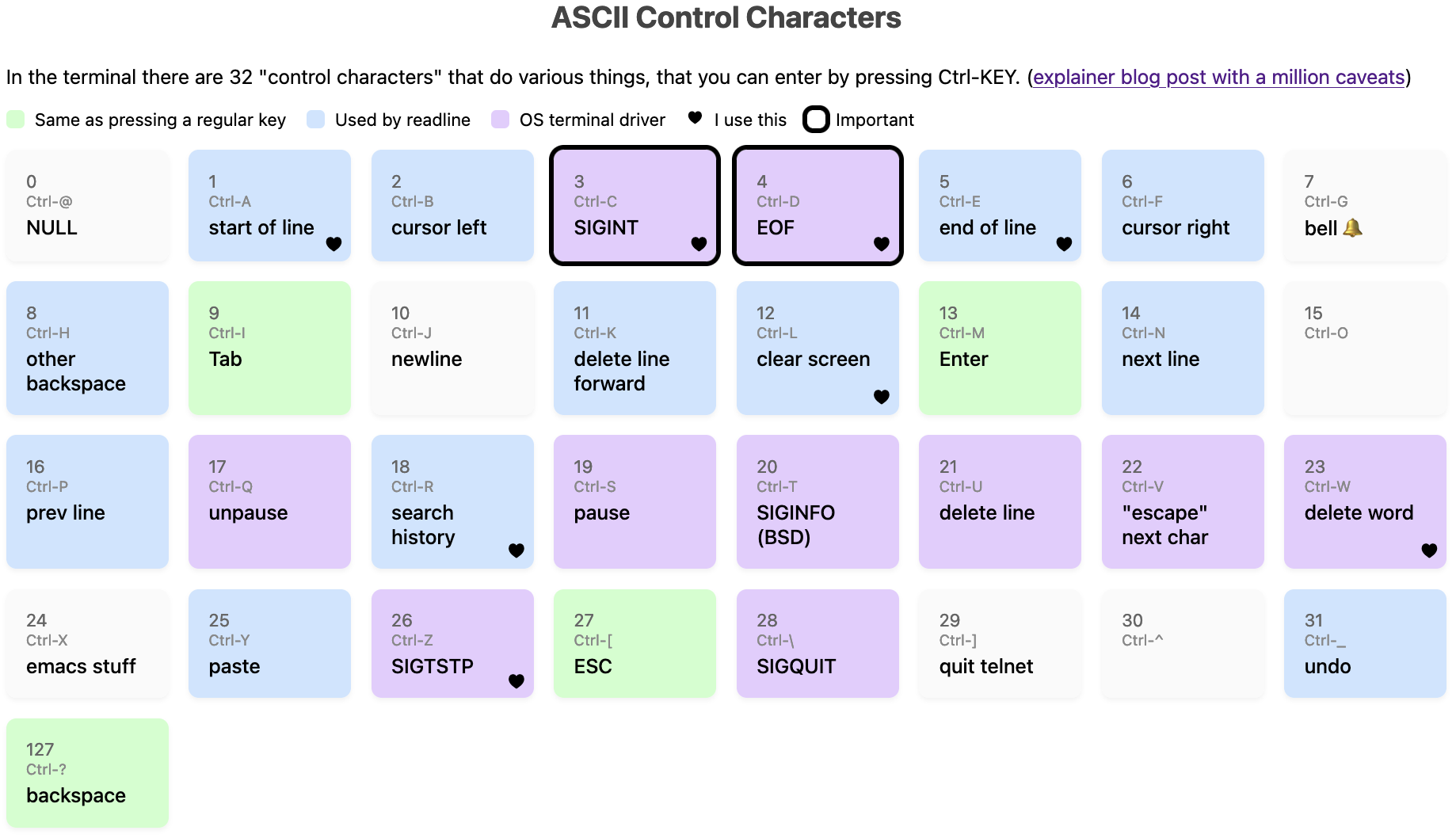

a table of ASCII control characters

Here’s a table of all 33 ASCII control characters, and what they do on my machine (on Mac OS), more or less. There are about a million caveats, but I’ll talk about what it means and all the problems with this diagram that I know about.

You can also view it as an HTML page (I just made it an image so it would show up in RSS).

different kinds of codes are mixed together

The first surprising thing about this diagram to me is that there are 33 control codes, split into (very roughly speaking) these categories:

- Codes that are handled by the operating system’s terminal driver, for

example when the OS sees a

3(Ctrl-C), it’ll send aSIGINTsignal to the current program - Everything else is passed through to the application as-is and the

application can do whatever it wants with them. Some subcategories of

those:

- Codes that correspond to a literal keypress of a key on your keyboard

(

Enter,Tab,Backspace). For example when you pressEnter, your terminal gets sent13. - Codes used by

readline: “the application can do whatever it wants” often means “it’ll do more or less what thereadlinelibrary does, whether the application actually usesreadlineor not”, so I’ve labelled a bunch of the codes thatreadlineuses - Other codes, for example I think

Ctrl-Xhas no standard meaning in the terminal in general but emacs uses it very heavily

- Codes that correspond to a literal keypress of a key on your keyboard

(

There’s no real structure to which codes are in which categories, they’re all just kind of randomly scattered because this evolved organically.

(If you’re curious about readline, I wrote more about readline in entering text in the terminal is complicated, and there are a lot of cheat sheets out there)

there are only 33 control codes

Something else that I find a little surprising is that are only 33 control codes –

A to Z, plus 7 more (@, [, \, ], ^, _, ?). This means that if you want to

have for example Ctrl-1 as a keyboard shortcut in a terminal application,

that’s not really meaningful – on my machine at least Ctrl-1 is exactly the

same thing as just pressing 1, Ctrl-3 is the same as Ctrl-[, etc.

Also Ctrl+Shift+C isn’t a control code – what it does depends on your

terminal emulator. On Linux Ctrl-Shift-X is often used by the terminal

emulator to copy or open a new tab or paste for example, it’s not sent to the

TTY at all.

Also I use Ctrl+Left Arrow all the time, but that isn’t a control code,

instead it sends an ANSI escape sequence (ctrl-[[1;5D) which is a different

thing which we absolutely do not have space for in this post.

This “there are only 33 codes” thing is totally different from how keyboard

shortcuts work in a GUI where you can have Ctrl+KEY for any key you want.

the official ASCII names aren’t very meaningful to me

Each of these 33 control codes has a name in ASCII (for example 3 is ETX).

When all of these control codes were originally defined, they weren’t being

used for computers or terminals at all, they were used for the telegraph machine.

Telegraph machines aren’t the same as UNIX terminals so a lot of the codes were repurposed to mean something else.

Personally I don’t find these ASCII names very useful, because 50% of the time the name in ASCII has no actual relationship to what that code does on UNIX systems today. So it feels easier to just ignore the ASCII names completely instead of trying to figure which ones still match their original meaning.

It’s hard to use Ctrl-M as a keyboard shortcut

Another thing that’s a bit weird is that Ctrl-M is literally the same as

Enter, and Ctrl-I is the same as Tab, which makes it hard to use those two as keyboard shortcuts.

From some quick research, it seems like some folks do still use Ctrl-I and

Ctrl-M as keyboard shortcuts (here’s an example), but to do that

you need to configure your terminal emulator to treat them differently than the

default.

For me the main takeaway is that if I ever write a terminal application I

should avoid Ctrl-I and Ctrl-M as keyboard shortcuts in it.

how to identify what control codes get sent

While writing this I needed to do a bunch of experimenting to digure out what various key combinations did, so I wrote this Python script echo-key.py that will print them out.

There’s probably a more official way but I appreciated having a script I could customize.

caveat: on canonical vs noncanonical mode

Two of these codes (Ctrl-W and Ctrl-U) are labelled in the table as

“handled by the OS”, but actually they’re not always handled by the OS, it

depends on whether the terminal is in “canonical” mode or in “noncanonical mode”.

In canonical mode,

programs only get input when you press Enter (and the OS is in charge of deleting characters when you press Backspace or Ctrl-W). But in noncanonical mode the program gets

input immediately when you press a key, and the Ctrl-W and Ctrl-U codes are passed through to the program to handle any way it wants.

Generally in noncanonical mode the program will handle Ctrl-W and Ctrl-U

similarly to how the OS does, but there are some small differences.

Some examples of programs that use canonical mode:

- probably pretty much any noninteractive program, like

greporcat git, I think

Examples of programs that use noncanonical mode:

python3,irband other REPLs- your shell

- any full screen TUI like

lessorvim

caveat: all of the “OS terminal driver” codes are configurable with stty

I said that Ctrl-C sends SIGINT but technically this is not necessarily

true, if you really want to you can remap all of the codes labelled “OS

terminal driver”, plus Backspace, using a tool called stty, and you can view

the mappings with stty -a.

Here are the mappings on my machine right now:

$ stty -a

cchars: discard = ^O; dsusp = ^Y; eof = ^D; eol = <undef>;

eol2 = <undef>; erase = ^?; intr = ^C; kill = ^U; lnext = ^V;

min = 1; quit = ^\; reprint = ^R; start = ^Q; status = ^T;

stop = ^S; susp = ^Z; time = 0; werase = ^W;

I have personally never remapped any of these and I cannot imagine a reason I

would (I think it would be a recipe for confusion and disaster for me), but I

asked on Mastodon and people said the most common reasons they used

stty were:

- fix a broken terminal with

stty sane - set

stty erase ^Hto change how Backspace works - set

stty ixoff - some people even map

SIGINTto a different key, like theirDELETEkey

caveat: on signals

Two signals caveats:

- If the

ISIGterminal mode is turned off, then the OS won’t send signals. For examplevimturns offISIG - Apparently on BSDs, there’s an extra control code (

Ctrl-T) which sendsSIGINFO

You can see which terminal modes a program is setting using strace like this,

terminal modes are set with the ioctl system call:

$ strace -tt -o out vim

$ grep ioctl out | grep SET

here are the modes vim sets when it starts (ISIG and ICANON are

missing!):

17:43:36.670636 ioctl(0, TCSETS, {c_iflag=IXANY|IMAXBEL|IUTF8,

c_oflag=NL0|CR0|TAB0|BS0|VT0|FF0|OPOST, c_cflag=B38400|CS8|CREAD,

c_lflag=ECHOK|ECHOCTL|ECHOKE|PENDIN, ...}) = 0

and it resets the modes when it exits:

17:43:38.027284 ioctl(0, TCSETS, {c_iflag=ICRNL|IXANY|IMAXBEL|IUTF8,

c_oflag=NL0|CR0|TAB0|BS0|VT0|FF0|OPOST|ONLCR, c_cflag=B38400|CS8|CREAD,

c_lflag=ISIG|ICANON|ECHO|ECHOE|ECHOK|IEXTEN|ECHOCTL|ECHOKE|PENDIN, ...}) = 0

I think the specific combination of modes vim is using here might be called “raw mode”, man cfmakeraw talks about that.

there are a lot of conflicts

Related to “there are only 33 codes”, there are a lot of conflicts where

different parts of the system want to use the same code for different things,

for example by default Ctrl-S will freeze your screen, but if you turn that

off then readline will use Ctrl-S to do a forward search.

Another example is that on my machine sometimes Ctrl-T will send SIGINFO

and sometimes it’ll transpose 2 characters and sometimes it’ll do something

completely different depending on:

- whether the program has

ISIGset - whether the program uses

readline/ imitates readline’s behaviour

caveat: on “backspace” and “other backspace”

In this diagram I’ve labelled code 127 as “backspace” and 8 as “other backspace”. Uh, what?

I think this was the single biggest topic of discussion in the replies on Mastodon – apparently there’s a LOT of history to this and I’d never heard of any of it before.

First, here’s how it works on my machine:

- I press the

Backspacekey - The TTY gets sent the byte

127, which is calledDELin ASCII - the OS terminal driver and readline both have

127mapped to “backspace” (so it works both in canonical mode and noncanonical mode) - The previous character gets deleted

If I press Ctrl+H, it has the same effect as Backspace if I’m using

readline, but in a program without readline support (like cat for instance),

it just prints out ^H.

Apparently Step 2 above is different for some folks – their Backspace key sends

the byte 8 instead of 127, and so if they want Backspace to work then they

need to configure the OS (using stty) to set erase = ^H.

There’s an incredible section of the Debian Policy Manual on keyboard configuration

that describes how Delete and Backspace should work according to Debian

policy, which seems very similar to how it works on my Mac today. My

understanding (via this mastodon post)

is that this policy was written in the 90s because there was a lot of confusion

about what Backspace should do in the 90s and there needed to be a standard

to get everything to work.

There’s a bunch more historical terminal stuff here but that’s all I’ll say for now.

there’s probably a lot more diversity in how this works

I’ve probably missed a bunch more ways that “how it works on my machine” might be different from how it works on other people’s machines, and I’ve probably made some mistakes about how it works on my machine too. But that’s all I’ve got for today.

Some more stuff I know that I’ve left out: according to stty -a Ctrl-O is

“discard”, Ctrl-R is “reprint”, and Ctrl-Y is “dsusp”. I have no idea how

to make those actually do anything (pressing them does not do anything

obvious, and some people have told me what they used to do historically but

it’s not clear to me if they have a use in 2024), and a lot of the time in practice

they seem to just be passed through to the application anyway so I just

labelled Ctrl-R and Ctrl-Y as

readline.

not all of this is that useful to know

Also I want to say that I think the contents of this post are kind of interesting

but I don’t think they’re necessarily that useful. I’ve used the terminal

pretty successfully every day for the last 20 years without knowing literally

any of this – I just knew what Ctrl-C, Ctrl-D, Ctrl-Z, Ctrl-R,

Ctrl-L did in practice (plus maybe Ctrl-A, Ctrl-E and Ctrl-W) and did

not worry about the details for the most part, and that was

almost always totally fine except when I was trying to use xterm.js.

But I had fun learning about it so maybe it’ll be interesting to you too.