Giving people the ability to shape the internet and their experiences on it is at the heart of Mozilla’s manifesto. This includes empowering people to choose how they search.

On Nov. 20, the United States Department of Justice (DOJ) filed proposed remedies in the antitrust case against Google. The judgment outlines the behavioral and structural remedies proposed by the government in order to restore search engine competition.

Mozilla is a long-time champion of competition and an advocate for reforms that create a level playing field in digital markets. We recognize the DOJ’s efforts to improve search competition for U.S. consumers. It is important to understand, however, that the outcomes of this case will have impacts that go far beyond any one company or market.

As written, the proposed remedies will force smaller and independent browsers like Firefox to fundamentally reexamine their entire operating model. By jeopardizing the revenue streams of critical browser competitors, these remedies risk unintentionally strengthening the positions of a handful of powerful players, and doing so without delivering meaningful improvements to search competition. And this isn’t just about impacting the future of one browser company — it’s about the future of the open and interoperable web.

Firefox and search

Since the launch of Firefox 1.0 in 2004, we have shipped with a default search engine, thinking deeply about search and how to provide meaningful choice for people. This has always meant refusing any exclusivity; instead we preinstall multiple search options and we make it easy for people to change their search engine — whether setting a general default or customizing it for individual searches.

We have always worked to provide easily accessible search alternatives alongside territory-specific options — an approach we continue today. For example, in 2005, our U.S. search options included Yahoo, eBay, Creative Commons and Amazon, alongside Google.

Today, Firefox users in the U.S. can choose between Google, Bing, DuckDuckGo, Amazon, eBay and Wikipedia directly in the address bar. They can easily add other search engines and they can also benefit from Mozilla innovations, like Firefox Suggest.

For the past seven years, Google search has been the default in Firefox in the U.S. because it provides the best search experience for our users. We can say this because we have tried other search defaults and supported competitors in search: in 2014, we switched from Google to Yahoo in the U.S. as they sought to reinvigorate their search product. There were certainly business risks, but we felt the risk was worth it to further our mission of promoting a better internet ecosystem. However, that decision proved to be unsuccessful.

Firefox users — who demonstrated a strong preference for having Google as the default search engine — did not find Yahoo’s product up to their expectations. When we renewed our search partnership in 2017, we did so with Google. We again made certain that the agreement was non-exclusive and allowed us to promote a range of search choices to people.

The connection between browsers and search that existed in 2004 is just as important today. Independent browsers like Firefox remain a place where search engines can compete and users can choose freely between them. And the search revenue Firefox generates is used to advance our manifesto, through the work of the Mozilla Foundation and via our products — including Gecko, Mozilla’s browser engine.

Browsers, browser engines and the open web

Since launching Firefox in 2004, Mozilla has pioneered groundbreaking technologies, championing open-source principles and setting critical standards in online security and privacy. We also created or contributed to many developments for the wider ecosystem, some (like Rust and Let’s Encrypt) have continued to flourish outside of Mozilla. Much of this is made possible by developing and maintaining the Gecko browser engine.

Browser engines (not to be confused with search engines) are little-known but they are the technology powering your web browser. They determine much of the speed and functionality of browsers, including many of the privacy and security properties.

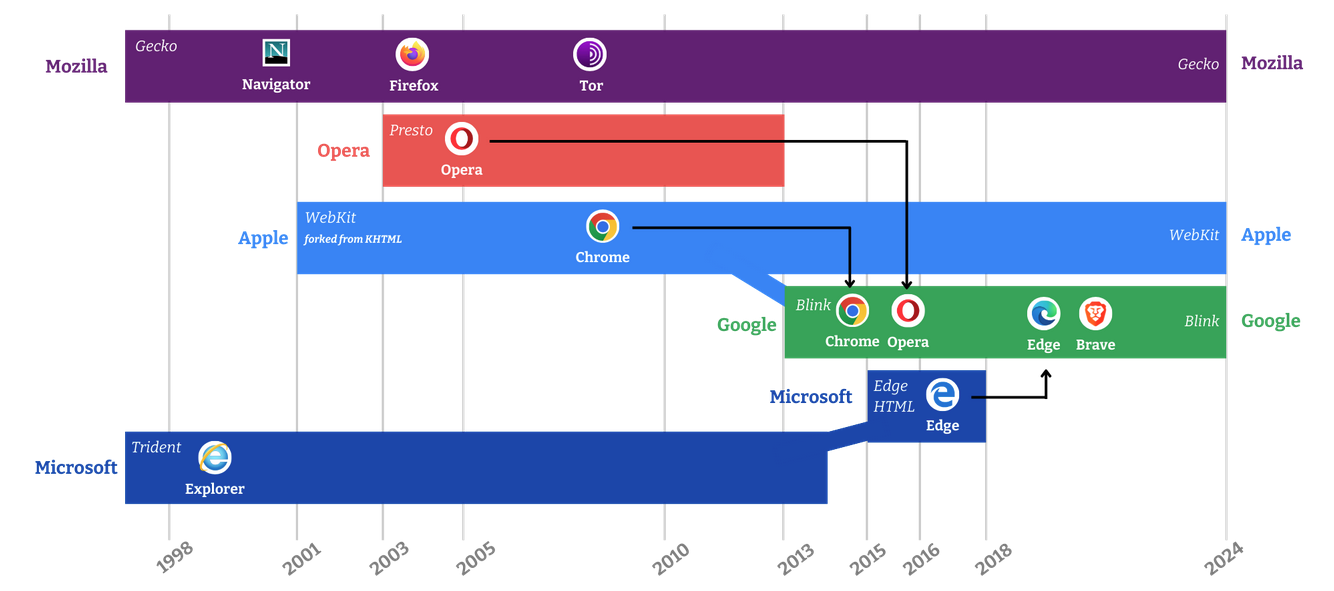

In 2013, there were five major browser engines. In 2024, due to the great expense and expertise needed to run a browser engine, there are only three left: Apple’s WebKit, Google’s Blink and Mozilla’s Gecko — which powers Firefox.

Apple’s WebKit primarily runs on Apple devices, leaving Google and Mozilla as the main cross-platform browser engine developers. Even Microsoft, a company with a three trillion dollar market cap, abandoned its Trident browser engine in 2019. Today, its Edge browser is built on top of Google’s Blink engine.

Remedies in the U.S. v Google search case

So how do browser engines tie into the search litigation? A key concern centers on proposed contractual remedies put forward by the DOJ that could harm the ability of independent browsers to fund their operations. Such remedies risk inadvertently harming browser and browser engine competition without meaningfully advancing search engine competition.

Firefox and other independent browsers represent a small proportion of U.S. search queries, but they play an outsized role in providing consumers with meaningful choices and protecting user privacy. These browsers are not just alternatives — they are critical champions of consumer interests and technological innovation.

Rather than a world where market share is moved from one trillion dollar tech company to another, we would like to see actions which will truly improve competition — and not sacrifice people’s privacy to achieve it. True change requires addressing the barriers to competition and facilitating a marketplace that promotes competition, innovation and consumer choice — in search engines, browsers, browser engines and beyond.

We urge the court to consider remedies that achieve its goals without harming independent browsers, browser engines and ultimately without harming the web.

We’ll be sharing updates as this matter proceeds.

The post Proposed contractual remedies in United States v. Google threaten vital role of independent browsers appeared first on The Mozilla Blog.